Overview

Chad Montrie

From the time Puritans settled in New England in the seventeenth century to the decades after the American Revolution, the region’s landscape was dotted by small mills that used water power for sawing wood, grinding grain, and carding wool to meet the needs of local communities. During the Industrial Revolution, however, corporate investors established mills and factories for manufacturing that harnessed water power on much greater scale and toward different ends, producing an extraordinary bounty of textiles, shoes, paper, and iron goods for markets near and far. Unlike the older mills, which relied on dams that could be lowered or removed during spring freshets and typically featured some version of a water wheel, the industrial enterprises depended on ever-higher permanent dams to make huge mill ponds that fed turbines to turn intricate belt systems.

The environmental impact of the new dams was immediate and dramatic, blocking migratory fish and flooding upstream meadows. Some local residents responded by removing flash boards and tearing down whole structures, or at least attempting to do so. Initially, they did this openly, empowered by both custom and law to take matters into their own hands and fix a “public nuisance” themselves. And when states passed laws making dam-breaking a crime, aggrieved residents continued to act surreptitiously and under cover of night. Others filed lawsuits against offending corporations but, over the course of the nineteenth century, courts increasingly interpreted riparian (water) law in favor of industry. The older principle of “reasonable use,” requiring users to do no significant harm to other users, gave way to the notion that water use for manufacturing had precedence over fishing and farming because it provided a greater public good.

As industrialization intensified and cities grew around the increasing number of mills and factories, many streams and rivers also became open sewers. Manufacturers dumped millions of gallons of waste into waterways where it mixed with copious amounts of raw municipal sewage, greatly worsening the frequency and severity of disease epidemics. Some local and state governments tried to address the problem by creating boards of health and passing pollution control laws. Yet even the strongest legislation had significant gaps, making exceptions for heavily industrialized and urbanized areas and providing for only limited enforcement. At the same time, corporations filed lawsuits of their own, questioning and subverting various aspects of the laws.

New England’s water-powered mills and factories significantly altered people’s relationship to nature as well, particularly the first group of operatives recruited from the countryside. These workers were primarily women, lured by the promises of comparatively high wages, corporate paternalism, and vibrant town culture. As they migrated from rural homesteads to urban boarding houses, however, the shift from agricultural work to industrial labor severed the more direct connection they had once had with the land and its flora and fauna through traditional homestead tasks. In response, the “mill girls” developed a working-class literary romanticism. They wrote and published poetry, stories, and essays in journals and newspapers that blended musing on metaphysical aspects of the natural world with criticism of noisy, filthy cities and regimented labor in prison-like mills.

Cite this overview:

Montrie, Chad. “Overview: Water Power, Industrial Manufacturing, and Environmental Transformation in 19th-Century New England.“ Energy History Online. Yale University. 2023. https://energyhistory.yale.edu/water-power-industrial-manufacturing-and-environmental-transformation-in-19th-century-new-england/

Library Items

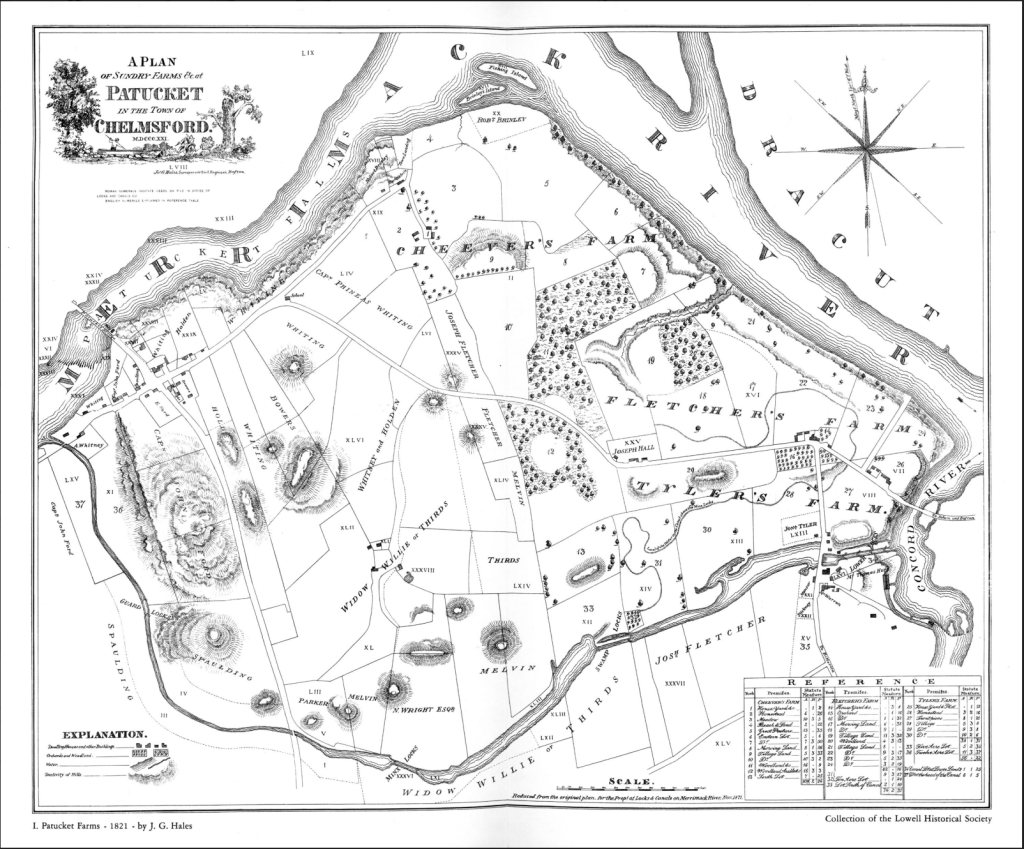

Plans of Lowell, MA, 1821 & 1832

Boston investors first attempted fully-integrated cotton textile manufacturing (both spinning and weaving) in Waltham, on the Charles River. Seeking more water power to expand their production, however, they decided to move to what was then East Chelmsford, on the Merrimack River. Other investors had built a transportation canal to skirt the Pawtucket Falls there and the “Boston Associates” turned that into a power canal and built the first mills along tributary canals. These two maps, one from 1821 and the other from 1832, show some of the “changes on the land” that the development of Lowell, MA entailed.

What does the 1821 map suggest about land ownership and land use before industrial manufacturing? How was the landscape organized? How did residents affect or remake natural features? How does the 1832 map reveal the older geography and land use? What modifications or additions happened between the first and the second?

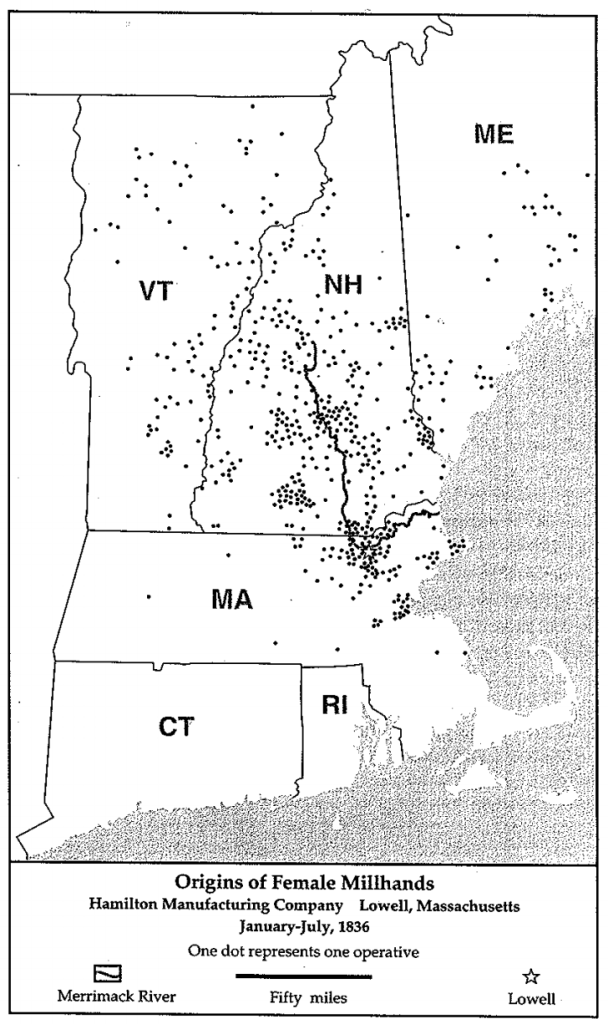

Origins of Female Millhands, Hamilton Manufacturing Company, Lowell, MA 1836.

Enticed by labor recruiters and granted permission by parents, many of the first operatives at industrial textile mills were young women from the distant countryside. Their families might be in need of cash to settle debt, buy land, or send a son to college. For the women, the mills offered a comparatively high wage (more so than teaching, the other main female occupation), relative independence (despite attentive presence of a boardinghouse keeper), as well as the lively culture of a bustling city.

What does this map show about the geographic origins of so-called “mill girls”? How far did they travel to take positions in the mills? What do you think that journey was like at the time?

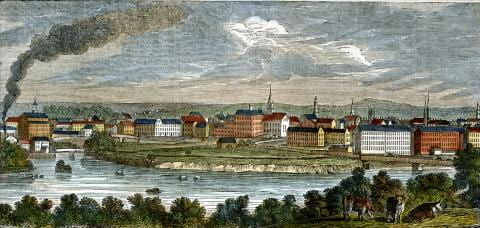

Edmund L. Barber, “East View of Lowell, Mass.” 1839.

This engraving by J.W. and Edmund Barber in 1839 shows the confluence of the Concord with the Merrimack River, looking south from the hills of what was then Dracut.

What aspects of agrarian land use and economy are present? What aspects of industrialization does it portray? How does the engraving represent the relationship between traditional rural life and modern urban industrial change?

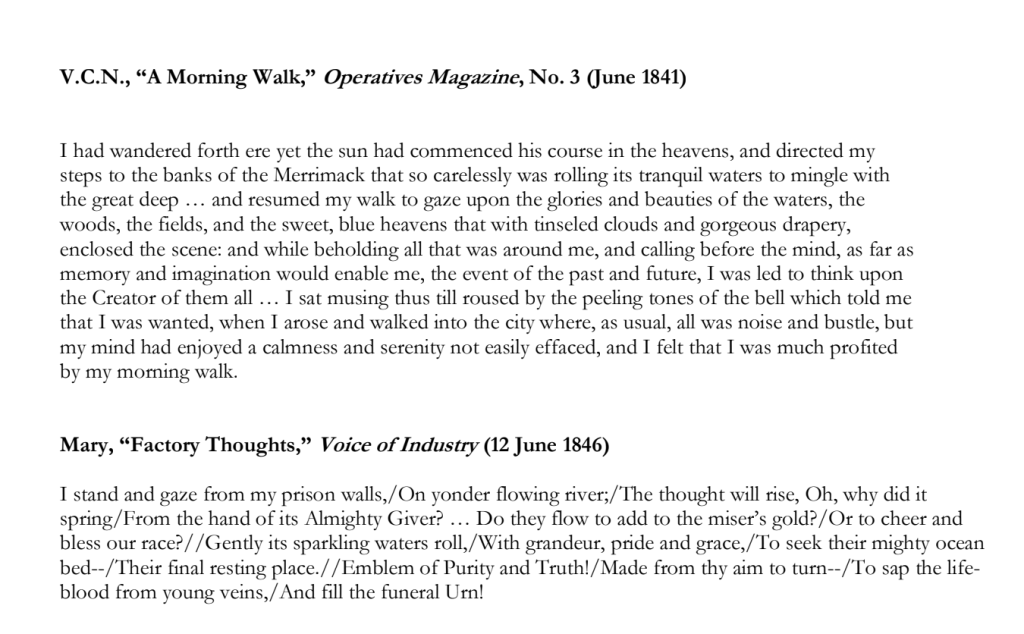

Female Millhands, Lowell Mills, Essay and Poem, 1840s

Female operatives began to arrive in places like Lowell in the 1820s. Many of them were not only literate but also relatively well-educated. In their time off from work some organized study circles and wrote poetry, stories, and essays that they published in literary journals, often using pseudonyms. Within a couple of decades “mill girls” also began to agitate for better wages and working conditions and a few crafted pieces for radical labor newspapers.

In her essay, where does V.C.N. go, and why? How does her experience relate to mill work and her connection to nature?

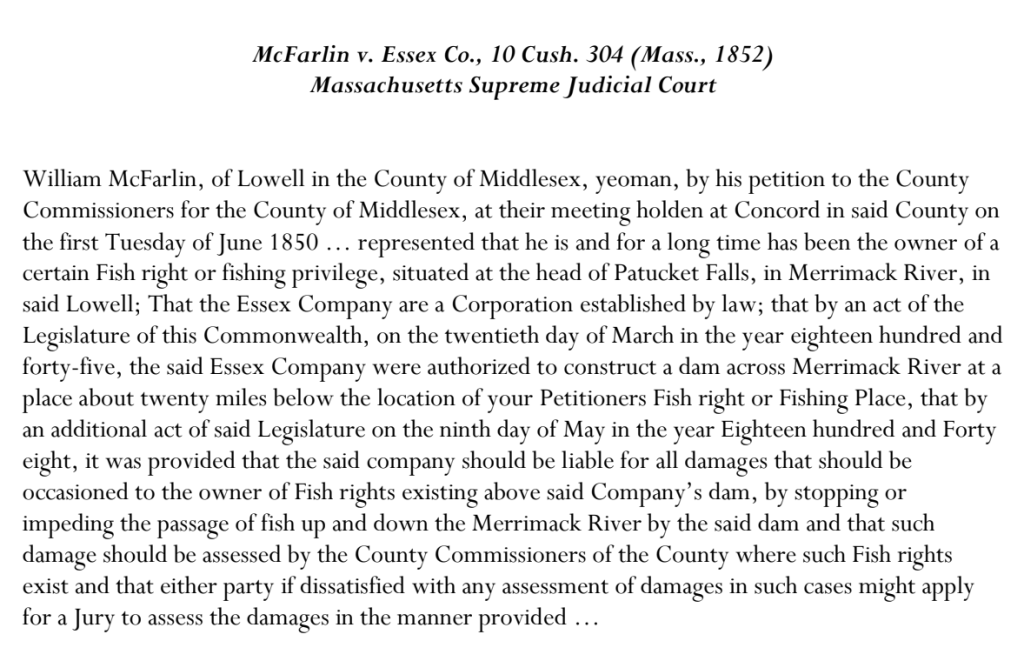

McFarlin v. Essex Co., Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, 1852.

How did the dam built by the Essex Co. on the Merrimack River affect William McFarlin’s livelihood? What did he do to get compensation for his loss? How did the State Court ruling show that ordinary people still had some right to use rivers and streams? How did it confirm the growing power of corporations over waterways?

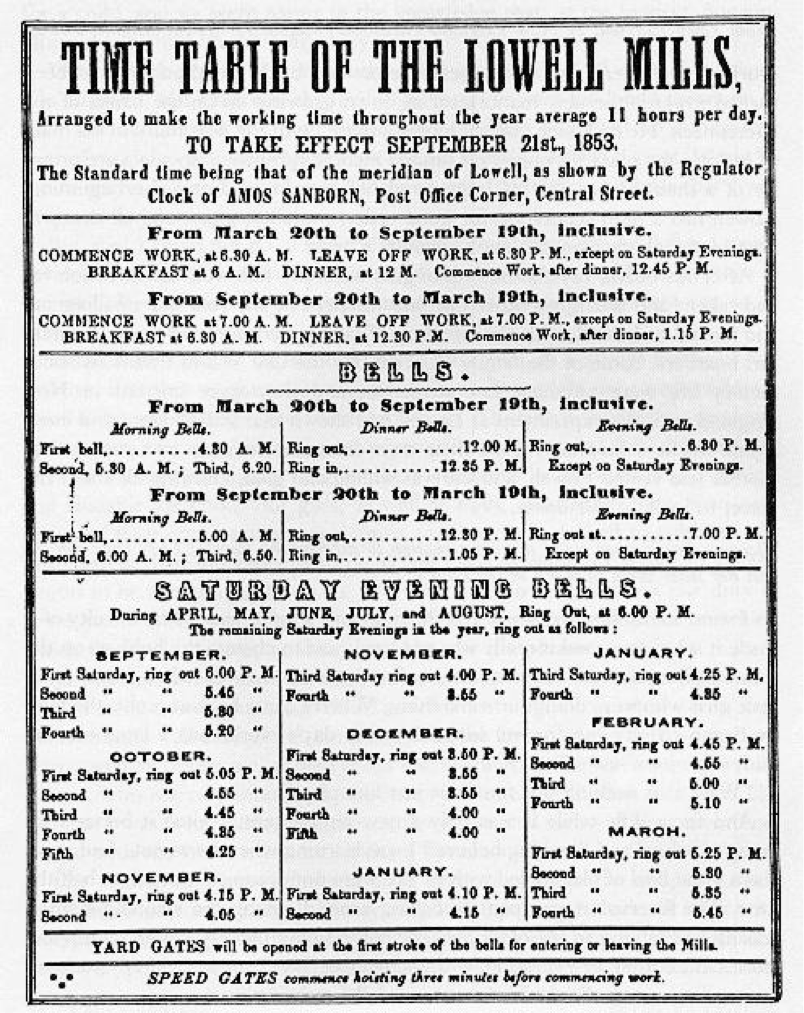

Lowell Mills Time Table, 1853

Before moving to places like Lowell, young women played a significant role in household production on their family homestead. That work happened both indoors and outdoors and was organized according to natural rhythms, the rising and setting of the sun, the needs of livestock, as well as the vagaries of weather and seasonal cycles. In the mills, however, the work day was ordered by hourly bells while impersonal overseers and indifferent machines established the work pace. Likewise, industrial labor was typically dull, repetitive, and (mostly) unchanging throughout the year.

What time did mill operatives begin and end their work day? When did they take breaks? How did these hours change throughout the year? Why did they change?

Anti-Dam Violence on the Merrimack River and its Tributaries, Fall 1859

What might explain residents’ anger about the Lake Company dam? What did they try to do to resolve the problems the dam was supposedly causing? What does this say about their view of industrial manufacturing and how the law applied to corporations? How did the corporations protect their interests?

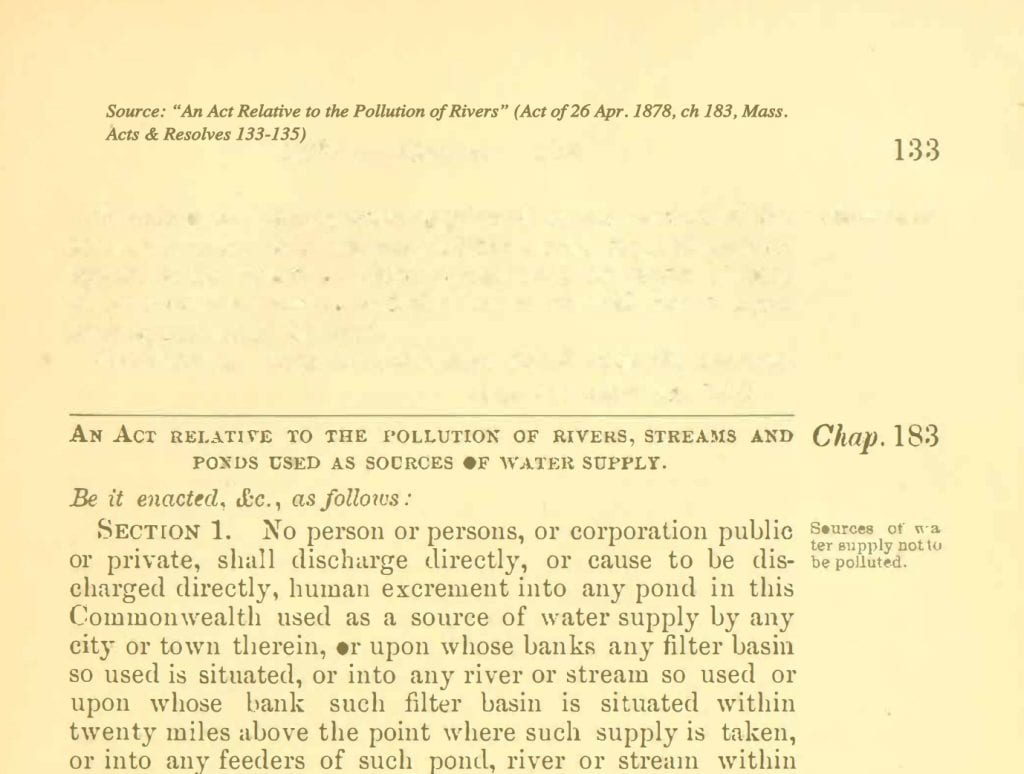

“An Act Relative to the Pollution of Rivers,” Massachusetts State Law, 1878.

During the nineteenth century, industrial corporations used waterways not only for power but also to dump waste. Cities, too, used local streams and rivers for disposing untreated sewage waste. Recognizing the worsening problem of filthy waterways, in 1878 the state of Massachusetts passed a pioneering pollution control law. Although the legislation was limited in scope, manufacturers filed lawsuits to challenge the law and they convinced the governor to significantly weaken the state board of health, the agency designated to enforce it.

What did the 1878 law prohibit? What exceptions did it make? Why did the legislature make those exceptions? Why do you think corporations organized to interfere with the law and its enforcement?

Additional Reading

Blewett, Mary H., ed. Caught Between Two Worlds: The Diary of a Lowell Mill Girl, Susan Brown of Epsom, New Hampshire. Lowell, MA: Lowell Museum, 1984.

Cumbler, John T. Reasonable Use: The People, the Environment, and the State, New England, 1790-1930. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Dublin, Thomas, ed. Farm to Factory: Women’s Letters 1830-1860. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

Montrie, Chad. The Myth of Silent Spring: Rethinking the Origins of American Environmentalism. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018.

Montrie, Chad. Making a Living: Work and Environment in the United States. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Steinberg, Theodore. Nature Incorporated: Industrialization and the Waters of New England. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994.

Author Bio

Chad Montrie is a professor in the History Department at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. His most recent book is The Myth of Silent Spring: Rethinking the Origins of American Environmentalism (University of California Press, 2018).