Overview

Paul Sabin

Who should develop and control electric power resources? In the early twentieth century, private utility companies struggled with government policymakers over how to build and make this vital new electrical infrastructure accessible to consumers. Long distance electrical transmission increasingly made complex and far-reaching electrical grids possible, enhancing the power of the entities that controlled the distribution of electricity. Economies of scale from operating larger grids, and the efficiency of establishing and maintaining a single infrastructural network, encouraged the development of urban and regional monopolies.

Corporate entrepreneurs like Samuel Insull of Chicago Edison built private utilities that consolidated disparate systems and sought to replace public municipal power ventures with private companies. Insull’s company purchased smaller rival enterprises and, by 1907, the newly renamed Commonwealth Edison effectively controlled all electric service in Chicago. In a 1910 speech, “The Obligations of Monopoly Must Be Accepted,” Insull articulated the rationale for a kind of public-private bargain that would characterize electrical service in many parts of the United States. Insull believed that private companies motivated by profit operated more efficiently than government bureaucracies guided by politics, but he recognized that a public interest in electricity provision. In exchange for monopoly control over a service area, Insull argued, private utilities would have to accede to public regulation of aspects of their operations and finances. Which aspects, and how much regulation– what was a fair return on investment– remained somewhat ambiguous in Insull’s proposal and are still hotly contested to the present day.

Others viewed the “natural monopoly” of electric power production from a quite different vantage point. During the 1920s, politicians like Nebraska Senator George Norris and Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot advocated for power networks under public control. Norris urged federal development of the promising Muscle Shoals dam site in Alabama, declaring it a public resource that should remain in government ownership. Norris rejected the idea that the site should instead be sold to an industrialist like Henry Ford, who sought to develop a new industrial city around the dam.

In Pennsylvania, Governor Pinchot called for a publicly directed, statewide transmission network to link coal-fired power plants in western Pennsylvania with electricity consumers elsewhere in the state. As the first head of the United States Forest Service, Pinchot previously had advocated for the scientific management of national forest reserves. According to supporters, the “Giant Power” system would make possible a “pool of power” blanketing Pennsylvania with a common electrical transmission network. They argued that a state network could use Pennsylvania’s coal more efficiently, lower electricity rates for consumers, and help electrify Pennsylvania’s isolated farms, thereby allowing people to remain in rural areas instead of emigrating to large cities.

During the high-flying 1920s, proposals by Norris, Pinchot and others for publicly controlled or financed electrical systems met with little success. In 1928, President Herbert Hoover vetoed Norris’s Muscle Shoals bill, calling public ownership contrary to “the ideals upon which our civilization has been based.” According to Hoover, federal power provision would “break down the initiative and enterprise of the American people.” Private electric utilities instead continued to consolidate and expand regional electrical monopolies, creating increasingly complex holding companies. Some of the first publicly owned stocks were in these electric companies and utility holding companies.

After the onset of the Great Depression, however, attitudes towards public power shifted dramatically. Private electric companies, with their perceived opaque structures, stock manipulation, and financial instability, were seen as major villains contributing to the nation’s economic crises. Insull’s highly leveraged business empire collapsed, wiping out the savings of hundreds of thousands of shareholders. Congress passed the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 to empower federal regulators to break up utility agglomerations like Insull’s, restrict operations to single states under the supervision of regulatory commissions, and force them to divest holdings to focus more narrowly on regulated services.

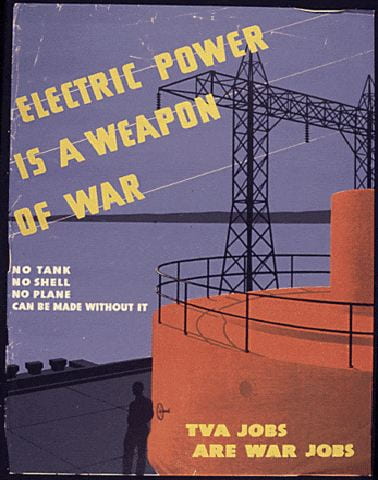

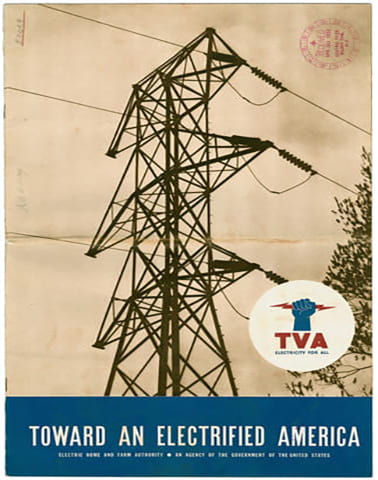

Other key elements of New Deal legislation reconfigured the provision and regulation of electric power in the United States. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), signed into law by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933, embraced George Norris’s vision by creating a public corporation to oversee power provision, flood control, and the development of agriculture and industry across several states in the Southeast. Wilson Dam at Muscle Shoals in Alabama, Norris’s longtime obsession, became one of dozens of TVA hydroelectric power sites. TVA later would diversify into nuclear, coal, and natural gas generation. To supporters, TVA symbolized the triumph of New Deal governance, showing how “public intelligence can operate most effectively through government and that government can be more efficient than business.” Conservative critics, however, called TVA a form of socialism and denounced its competition with private energy companies. Wendell Willkie, president of the Commonwealth & Southern Corporation, fought TVA’s takeover of his utility company’s transmission lines and TVA’s entry into direct electric service provision in the South. Willkie’s fight against TVA and the New Deal led him to leave the Democratic Party to run unsuccessfully against Roosevelt as the Republican nominee in the 1940 presidential election.

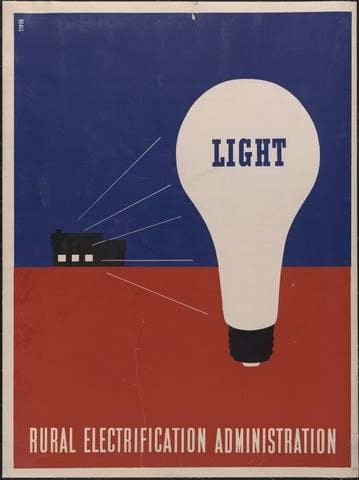

The Rural Electrification Act of 1936 gave the federal government responsibility for bringing electricity to rural areas across the country, implementing aspects of Pennsylvania’s “Giant Power” vision. Rural electric cooperatives, established as nonprofit organizations funded and governed by their members, borrowed money from the federal government to extend rural transmission lines and connect them to farms and homes. The number of farms in the United States with access to electricity jumped from around 11% in the mid-1930s to around 97% by the late 1950s. More than half of these electrified homes and farms received electrical service from utilities financed by the Rural Electrification Administration. Rural electrification brought new electric lights, electric appliances, and electric powered farm equipment to rural America.

By the end of the 1950s, the electrical system of the United States had become a national assemblage of public and private electrical networks. In parts of the country, rural electrical cooperatives or public service providers like the Tennessee Valley Authority provided electrical service. In other areas, private utilities, such as California’s Pacific Gas and Electric and Southern California Edison, delivered electricity through corporate monopolies overseen by state public utility commissions. These private companies pursued shareholder profits in a highly regulated environment. State utility commissions helped set utility rates, investments, and service. This system for regulating private utility monopolies would remain largely untouched until the late 1970s, when policymakers sought to use legal reforms like the Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act of 1978 (PURPA), to encourage energy conservation, price competition, and new sources of energy supply.

Cite this overview:

Sabin, Paul. “Overview: Electricity and the Public Good: Private-Public Power Debates in the 1920s-30s.” Energy History Online. Yale University. 2023. https://energyhistory.yale.edu/electricity-and-the-public-good-private-public-power-debates-in-the-1920s-30s/.

Library Items

Rural Electrification Posters, 1930s-1940s (gallery)

With the passage of the Rural Electrification Act in 1936, the federal government sought to extend the reach of electrical systems into the countryside. The ability to run electrical appliances, including lighting, and to power rural industries had a profound impact on rural communities. In the 1930s and 1940s, the Rural Electrification Administration celebrated these transformations with a series of promotional posters designed by the artist Lester Beall.

Tennessee Valley Authority, World War II Posters, 1942-43 (gallery)

During World War II, hydroelectric dams operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority powered crucial war industries, including factories producing airplanes and bombs. TVA’s hydropower also served the secret nuclear complex at Oak Ridge, Tennessee as part of the Manhattan Project.

How did these World War II-era posters lay the groundwork for the popular celebration of TVA and government planning and development in the post-war period?

Editorial, “Muscle Shoals– Ours,” The Nation, 1924

Muscle Shoals is a site on the Tennessee River in Alabama where President Woodrow Wilson authorized a hydroelectric dam during World War I to produce nitrates for munitions. The war ended before the dam was finished and during the 1920s a dispute erupted over the future use of the site and the dam.

Should the dam be transferred to private developers, such as Henry Ford, who proposed to use the dam to produce fertilizer and electricity? Or should the dam remain in public hands, owned and managed by a government agency?

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “A Suggestion for Legislation to Create the Tennessee Valley Authority,” 1933

In 1933, as a part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal agenda, Congress chartered the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the first large federal regional planning project. The TVA provided electrical power, flood control, and economic development to Tennessee and other deep south states hit hardest by the Depression. In this April 1933 address, Roosevelt calls on Congress to approve of the TVA; Congress did so a month later, and it remains in operation to the present day.

TVA, “Toward an Electrified America,” 1934

Published a year after the agency’s founding, this brochure offers an overview of how the TVA promoted electricity consumption in rural areas. The brochure puts a spotlight on the Electric Home and Farm Authority, a division of the TVA that provided financing plans to purchasers of electrical and gas appliances for use at home and work.

What does the brochure tell us about the relationship between the federal government and private electricity consumption? How might a program like the Electric Home and Farm Authority have helped families through the Great Depression? What does the document tell us about gender norms and their relationship to consumption and labor during the 1930s?

John D. Battle, Executive Secretary of the National Coal Association, Statement on Tennessee Valley Authority, 1935

In his 1935 Congressional testimony, John D. Battle, Executive Secretary of the National Coal Association, criticized the Tennessee Valley Authority’s plans to produce and distribute hydroelectric power. The federal government should not compete directly with private energy producers and utility companies, Battle argued.

How did Battle distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate functions of the federal government? How did the problem of unemployment in the coal industry justify his opposition to government-led energy production?

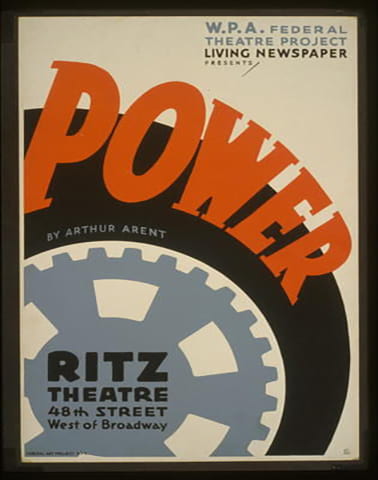

W.P.A. Federal Theatre Project Living Newspaper, “Power” by Arthur Arent

The New Deal-era Works Progress Administration funded the Federal Theater Project between 1935-1939 as a way to support cultural artistic production and provide employment for workers in the theater business. Many of the theater projects embraced an explicitly political perspective. In “Power,” playwright Arthur Arent made the case for government-sponsored energy production, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, and rural electrical cooperatives as alternatives to inadequate and costly service offered by utility companies.

Additional Reading

Phillips, Sarah. This Land, This Nation: Conservation, Rural America and the New Deal. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Nye, David. Consuming Power: A Social History of American Energies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997.

McCraw, Thomas K. TVA and the Power Fight, 1933-1939. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1971.

Ekbladh, David. “‘Mr. TVA’: Grass-Roots Development, David Lilienthal, and the Rise and Fall of the Tennessee Valley Authority as a Symbol for U.S. Overseas Development, 1933–1973,” Diplomatic History 26, no. 3 (July 2002): 335–374.

Selznick, Philip. TVA and the Grass Roots: A Study of Politics and Organization. Classics ed. New Orleans: Quid Pro Books, 2011.

Tobey, Ronald. Technology as Freedom: The New Deal and the Electrical Modernization of America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

White, Richard. The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River. New York: Hill & Wang, 1995.

Cater, Casey. Regenerating Dixie: Electric Energy and the Modern South. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019.

Riggs, John A. High Tension: FDR’s Battle to Power America. New York: Diversion Books, 2020.

Author Bio

Paul Sabin is the Randolph W. Townsend, Jr. Professor of History at Yale University, where he teaches and writes about environmental and energy history. He is the author of Public Citizens: The Attack on Big Government and the Remaking of American Liberalism (W.W. Norton, 2021), The Bet: Paul Ehrlich, Julian Simon and Our Gamble over Earth’s Future (Yale University Press, 2013), and Crude Politics: The California Oil Market, 1900-1940 (University of California, 2005).