Overview

Gabriel Lee

The era of large-scale hydroelectric dam building spanned roughly four decades, from the 1930s through the 1960s. Symbolically, the era commenced with Hoover Dam’s dedication in 1935. Hoover, however, was a culmination of larger technological and political changes.

Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century, a combination of large dams, powerful turbines, and high-tension transmission lines enabled electrical utilities to harness enormous energy from running water and to distribute power more than a hundred miles from electric generators. Hydroelectric power, or “white coal,” offered an alternative to fossil fuel-powered electric energy that, for progressive-age Americans, promised social and environmental benefits. Power dams offered cheap, pollution-free, and renewable energy sources. Progressives promoted centralized federal dams as a means to establish publicly-owned power and to electrify rural areas, making dams prominent objects of antimonopoly politics and social reform.

But hydropower was also an engine of developmental politics. Over the first third of the twentieth century, planners began designing dams that combined their hydropower function with other societal goals, such as navigation, flood control, irrigation, and urban water supply. Selling the potential energy held in a large reservoir could help these large-scale water management projects pay for themselves. Particularly in the American West, hydropower came to underwrite the large-scale multipurpose dam projects that drove regional growth.

The awesome scale of Hoover Dam captivated contemporaries: double the volume of any prior dam, Hoover held back the world’s largest artificial lake (Lake Mead) and increased, at a single site, the hydropower supply of the American West by nearly fifty percent. It was the world’s first “high dam,” made possible by an interstate agreement, federal involvement through the Reclamation Bureau, and Southern California’s energy market. Approved in 1928 but built during the early years of the Great Depression, Hoover Dam linked job creation and economic growth through public works, making it a model for further federal involvement in regional-scale multipurpose dam projects.

In the 1930s, emergency funds brought multiple large-scale dam projects to realization. The Central Valley Project in California, which rearranged the state’s hydraulic system, dwarfed the Hoover Dam. On the Columbia River basin, two major dams—Bonneville and Grand Coulee—brought dreams of economic wealth to the little developed Pacific Northwest. Grand Coulee alone could generate 2,253 megawatts of power, roughly equivalent to the entire Tennessee Valley Authority. These and other Depression-era dams produced immense energy in search of markets just in time for World War II. They powered booming industrial growth for wartime manufacturing that permanently reorganized regional economies around energy-intensive industries such as aluminum, aircraft production, and the finished electrical appliances that fueled new demands for residential power.

Over the postwar decades, the use of public works as a mode of economic stimulus dramatically expanded. Between 1945 and 1975, the Reclamation Bureau and Army Corps of Engineers built more than 150 dams on the Columbia, Missouri, and Colorado River basins. They transformed each of these river systems into a staircase of energy-generating reservoirs. Many of these dams, exemplified by the 710-foot-high Glen Canyon Dam, were enormous. Collectively, they helped complete the West’s transformation into an agricultural and industrial powerhouse.

Most Americans lauded the large-scale environmental transformations necessary to harness the power of rivers. Building regional-scale power dams exhibited an unparalleled engineering aptitude that produced rapid economic growth. Mid-century Americans believed them so successful that hydropower dams formed a basis for the country’s postwar foreign policy of economic development. But large power dams were also contested spaces that raised a number of thorny questions: Who should benefit from federally-built power plants? Should public agencies or private energy companies sell the power and determine rates? How would dramatically transformed river systems accommodate a multitude of legal claims to the river’s water and fisheries? Were dams more environmentally destructive than they were economically productive? Many of these questions remain with us.

Cite this overview:

Lee, Gabriel. “Overview: The Big Dam Era.” Energy History Online. Yale University. 2023. https://energyhistory.yale.edu/the-big-dam-era/.

Library Items

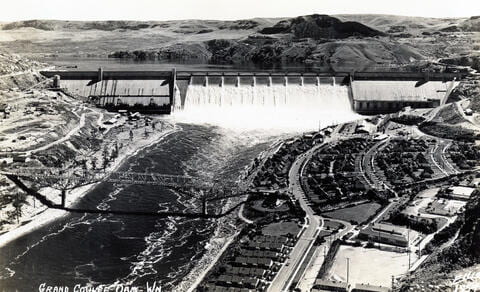

Grand Coulee Dam (gallery)

Grand Coulee Dam was constructed on the Columbia River in the State of Washington between 1933 and 1942, with a goal of providing irrigation, flood control, and electricity generation. These photos from the University of Washington capture aspects of the dam’s construction and its subsequent appreciation and celebration.

What strikes you in the images of the dam?

Celilo Falls Fishing on the Columbia River, Oregon (gallery)

Celilo Falls, on the Columbia River at the border of the states of Washington and Oregon, was an important tribal fishing site for native peoples for centuries. At this stretch of the river, the stream contracts into two stretches of narrow water, one short and one long, funneling migrating salmon into a single channel and making easy, if dangerous, fishing possible. Celilo Falls is believed to be one of the oldest continuously inhabited native communities on the North American continent; it was destroyed in 1957 to construct The Dalles Dam.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Boulder Dam Dedication Speech, Sept. 30, 1935

In September 1935, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt traveled to Boulder Dam (later renamed Hoover Dam) to celebrate the monumental feat of engineering, accomplished through public and private partnership.

How did Roosevelt weave the story of Boulder Dam into a vision for national progress? How does Roosevelt characterize what existed before the dam, and its utility, and what would come afterwards? What are some of the different benefits cited by Roosevelt as resulting from the dam’s completion?

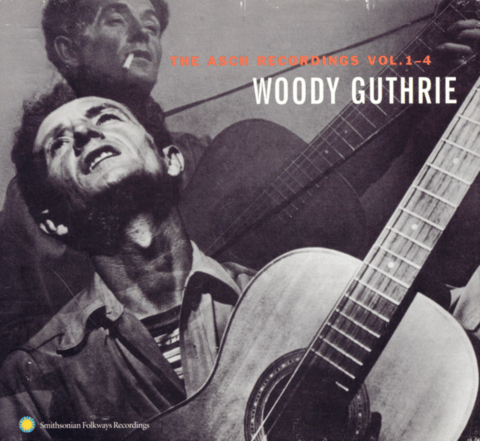

Woody Guthrie, “Grand Coulee Dam,” Lyrics, 1941

In May of 1941, the federal government employed folk legend Woody Guthrie to write songs to promote government-built hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest. Along with such classics as “Roll on Columbia” and “Pastures of Plenty,” Guthrie penned “Grand Coulee Dam” during this period, set to the tune of “Wabash Cannonball.” Built under the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration beginning in 1933, the Grand Coulee Dam is a concrete gravity dam that provides hydroelectric power and irrigation water.

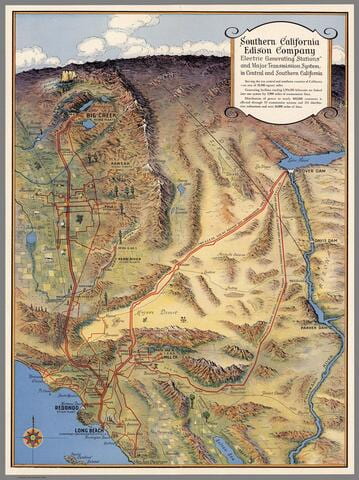

Southern California Edison Co. Transmission System Map, 1947

Historians often describe the growing cities of the 19th and 20th centuries in imperial terms. Metropolitan powers like New York, Chicago, and later Los Angeles reached out across rural landscapes to gather resources to fuel their development.

Consider this 1947 map of transmission lines linking the Los Angeles area to hydroelectric projects in northern California and Nevada.

What relationships did these systems establish between urban and rural communities? What kind of booster visions, and ideas about land and water, conjured the plans into being?

Upper Columbia United Tribes, “Grand Coulee and the Forgotten Tribe”

When the Grand Coulee Dam was completed in 1942, it created Lake Reservoir, a 130-mile lake that flooded upstream lands and valuable fishing sites. What would this mean for the Spokane Tribe that lived along the river? What represents justice in the development of the river’s resources?

This short retrospective film from 2016 recounts the sense of cultural and economic loss felt by the Spokane, and their enduring anger at a lack of compensation for these damages.

Additional Reading

Billington, David P. and Donald C. Jackson. Big Dams of the New Deal Era: A Confluence of Engineering and Politics. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006.

Dick, Wesley Arden. “When Dans Weren’t Damned: The Public Power Crusade and Visions of the Good Life in the Pacific Northwest in the 1930s.” Environmental Review: ER 13, no. 3/4 (Autumn-Winter 1989): 113–53.

Dodd, Douglas W. “Boulder Dam Recreation Area: The Bureau of Reclamation, the National Park Service, and the Origins of the National Recreation Area Concept at Lake Mead, 1929-1936.” Southern California Quarterly 88, no. 4 (Winter 2006): 431–73.

Duchemin, Michael. “Water, Power, and Tourism: Hoover Dam and the Making of the New West.” California History 86, no. 4 (January 2009): 60–89.

Hundley, Jr., Norris. The Great Thirst: Californians and Water, 1770s-1990s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Pisani, Donald J. Water and American Government: The Reclamation Bureau, National Water Policy, and the West, 1902-1935. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Worster, Donald. Rivers of Empire: Water Aridity, and the Growth of the American West. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Author Bio

Gabriel Lee is currently the Cassius Marcellus Clay postdoctoral fellow in environmental history at Yale University. He is working to finish his first book manuscript, a history of concrete during the Progressive Era, which examines the environmental and social politics of urban infrastructure, industrial architecture, automobile highways, and federal dams.