Overview

Christopher Jones

Coal can easily appear mundane to modern eyes—an inferior product from a bygone era. Yet this black, sooty, heavy rock provided a crucial underpinning for the Industrial Revolution: the development of industrial economies based on manufacturing from the late 18th century onwards. The rise of coal in the modern era was a global phenomenon, taking place in earnest in Britain beginning in the mid-18th century, the United States and Germany in the early 19th century. Most other nations have followed suit since, with China and India becoming the world’s leading consumers of coal in the present century.

Industrialization, a slow and uneven process, helped bring enormous social changes, including the rise of factory work, the move from rural farms to giant cities, the production and consumption of countless new goods, and the spread of global inequality and modern empires.

Coal was a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for large-scale industrialization. It was necessary because industrialization required more concentrated forms of energy than previously available. Human and animal muscle, rivers with falling water, trees to burn, wind to turn windmills and fill sails—these energy sources were limited in their local availability and in their energy density.

Yet many regions in the world had access to coal and did not industrialize. Coal is not, and never has been, an independent or sufficient factor. People made choices and had to decide if, whether, and how to use coal. Advocates (and opponents) included well-known entrepreneurial capitalists, government officials, and factory operators as well as less often considered homeowners, workers, journalists, scientists, and authors.

The most visible uses of coal in the United States were to manufacture iron, steam engines, and railroads. Americans had made iron before coal using charcoal—wood burned in the absence of oxygen. But charcoal required lots of wood, and this limited its total supply. With coal, iron production could expand enormously, giving rise to further industries that, in turn, used more coal, such as steam engines.

Built of iron or steel, steam engines provided a new and flexible source of power for growing factories. Previously, factories relied on falling water for power, but there were only so many rivers and they often froze in the winter. Steam engines allowed industrial production to grow regardless of local power sources. Often this meant clustering in cities. And by combining steam engines with thousands of miles of iron tracks, the railroad offered the quintessential image of an industrializing nation. The “Iron Horse” spanned the continent, delivered people and goods at high speeds regardless of rain, snow, or mud, and built financial fortunes for a lucky few. Some Americans spoke about the annihilation of time and space along railroads, others bemoaned the power of railroad barons to charge high rates, some perished in fiery crashes, and others struggled to adjust to the disorienting change of pace railroads ushered in.

Railroads and steam engines may have been the “big tech” of the nineteenth century, but a more humble use of coal mattered greatly as well: its consumption in homes. In fact, before railroads were widespread and when only a handful of steam engines were in operation, thousands of urban homeowners were using coal to heat their houses and cook their food. This gave coal dealers an important early market before industrial users. Adopting coal in the home involved more than just substituting coal for wood. It often meant purchasing a new stove, an expensive proposition that changed the look and feel of the home. This change in the household had uneven effects for men and women. Chopping, splitting, stacking, and hauling firewood was often labor performed by men, while the cleaning of wood and then coal-fired stoves fell to women. Women also were typically responsible for cleaning the sootier smoke from coal fires. Less work for men could mean more work for women. Homes looked different, smelled different, and required different divisions of labor once their owners adopted coal.

Finally, coal found its way into countless industries that generated a growing economy. Textile factories could use steam engines to increase output; construction projects could take advantage of cheaper iron bars, nails, and screws; and entirely new industries (such as making stoves for homeowners to burn coal) were made possible by cheap and abundant coal. Whether it was making a product, sending it to market, or constructing a building, coal played an increasingly important role in making it happen.

Cite this overview:

Jones, Christopher. “Overview: Rise of Coal in the Nineteenth-Century United States.” Energy History Online. Yale University. 2023. https://energyhistory.yale.edu/rise-of-coal-in-the-nineteenth-century-united-states/.

Library Items

Charles Cist Compares Cincinnati and Pittsburgh in 1841

The author Charles Cist noted in 1841 the ways that coal had transformed Pittsburgh into a “dense cloud of darkness and smoke” with clanking chains and “jarring and grinding” machinery. The soot fell like snowflakes on Pittsburgh’s inhabitants. Cist predicted that Cincinnati, which was still powered largely by water and wood, also would soon turn fully to coal.

How does Cist compare Cincinnati to the “perfect hive” of Pittsburgh?

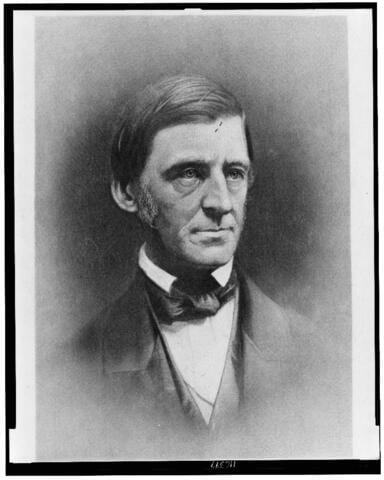

Ralph Waldo Emerson on steam and coal, 1860

In 1860, the American writer Ralph Waldo Emerson published “The Conduct of Life,” a widely read collection of essays on topics such as beauty, power, culture, and wealth. Emerson’s reflections included commentary on the power of steam and coal, and the ways in which people harnessed these tools to transform the natural world and society.

How does Emerson see the role of technology and invention in the creation of wealth?

What does Emerson mean when he calls coal a “portable climate”?

W. Stanley Jevons, “The Coal Question,” 1865

In his 1865 book, “The Coal Question; An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines,” British economist William Stanley Jevons warned that Britain would exhaust the coal supplies that were fueling its growth and prosperity. He argued that increased efficiency in consumption would not reduce demand for energy, but rather would spur increased use and further deplete supplies.

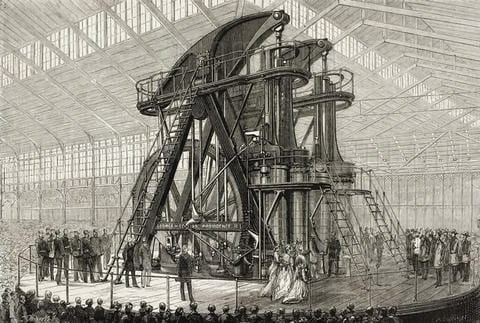

William Dean Howells describes the Corliss steam engine, American Centennial Exhibition, 1876

At the 1876 American Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, a mighty Corliss steam engine was ceremoniously unveiled on opening day by President Ulysses Grant and Emperor Pedro II of Brazil. The 1400 horsepower engine powered all the other mechanical devices on display in the grand Machinery Hall. Earlier versions of the engine, whose design George Corliss patented in 1849, helped make possible the transition from water power to steam through their greater fuel efficiency, uniform motion, and ability to handle changes in load.

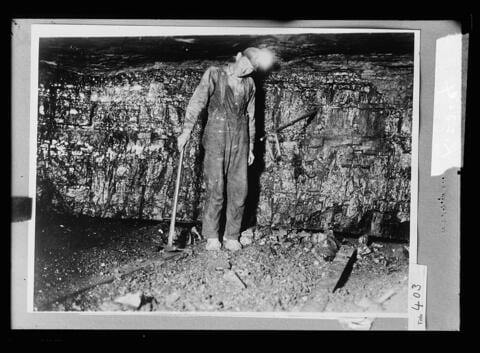

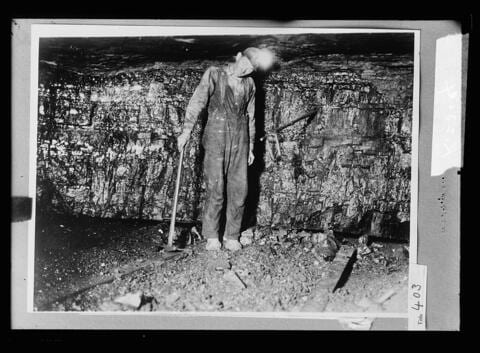

Coal Miners Working Inside the Mine, 1908 (gallery)

Coal miners worked long hours inside the mine, often traveling by elevator deep underground to extract coal from the coal seam. In the nineteenth century, miners worked largely by hand alongside animal labor. As new technology emerged, underground mining increasingly depended on heavy machinery.

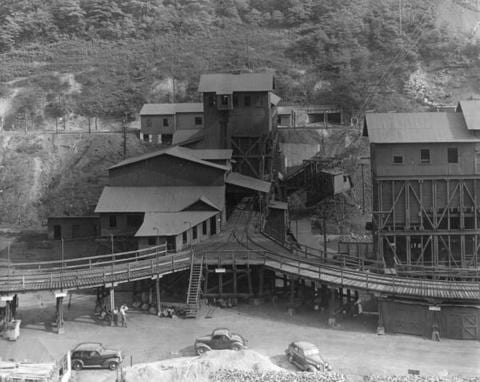

Stonega Coal Mines and Company Camp, 1915-1930 (gallery)

Company towns like the Stonega coal camp near the town of Appalachia, Virginia included the mine and related mining facilities, as well as houses, a commissary (company store), and amusement hall. All was owned by the company. The company towns doubled as a way to attract and support workers and as a means to subject employees and their families to company control.

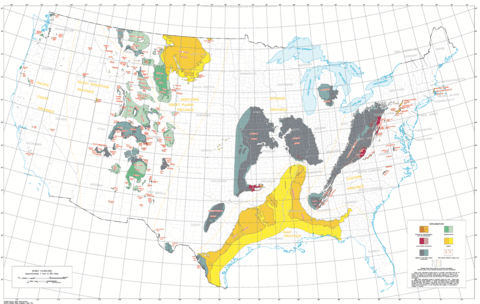

Coal Fields of the Conterminous United States

Where are the major coal fields in the United States located?

How might the geography of coal have shaped the rise of the coal mining industry– its economics, culture, and politics?

Additional Reading

Adams, Sean Patrick. Home Fires: How Americans Kept Warm in the Nineteenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

Andrews, Thomas G. Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Dublin, Thomas, and Walter Licht. The Face of Decline: The Pennsylvania Anthracite Region in the Twentieth Century. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005.

Jones, Christopher F. Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Shulman, Peter A. Coal and Empire: The Birth of Energy Security in Industrial America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

Stradling, David, and Peter Thorsheim. “The Smoke of Great Cities: British and American Efforts to Control Air Pollution, 1860-1914.” Environmental History 4, no. 1 (1999): 6–31.

Thesing, William B, ed. Caverns of Night: Coal Mines in Art, Literature, and Film: A Collection of Essays. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

Author Bio

Christopher Jones is an associate professor of history in the School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies at Arizona State University. He is the author of Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Harvard, 2014), which analyzes the causes and consequences of America’s first energy transitions.