Overview

Ann Norton Greene

After human muscle power, domesticated animals provided the most accessible, economical and efficient source of power available to Americans in the nineteenth century. The hallmarks of early nineteenth century industrialization—the transportation revolution in infrastructure, commercial expansion, rising agricultural production and productivity, and urban growth—all depended on the growth and intensification in the use of animal power. Until the 1870s, animals delivered the majority of power utilized by Americans; in 1900, animals still accounted for a third of all power consumed.

The lasting significance of animal power may surprise anyone who believes that industrialization was a linear process of machines replacing muscle, or that the steam engine displaced all other forms of power. In practice, animals like horses, mules and oxen were necessary complements to the newer kinds of power. Steam technology had great power and potential, but it was primarily effective in stationary engines, or in railroad locomotives operating over long distances. Work animals continued to provide functions, flexibility and efficiency that steam engines lacked for many decades or would never replace. In many instances, only the advent of electricity and internal combustion engines could displace horses from their critical role.

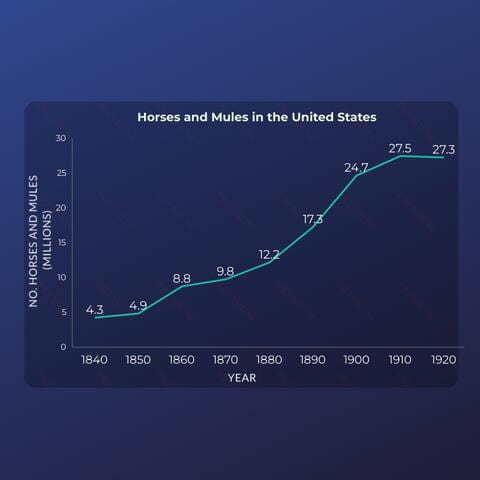

Consequently, the use of animal power increased substantially, rather than declining, during the period from the early nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. The draft animal population–the vast majority of which were horses and mules—grew six-fold between 1840 and 1900, from four to twenty-four million. This outpaced the growth in human population, which merely tripled during those same decades. By 1900, there was one horse or mule for every three humans in the United States. The majority of work animals lived and worked in cities and their surrounding hinterlands. The greatest uses of animal power were in agriculture and transportation.

In agriculture, mechanization increased the use of animal power. Up to the early 19th century, animal power had played a small role in agriculture, used mostly for clearing and plowing. Oxen commonly did arduous tasks that required power rather than speed. But planting, cultivating and harvesting were still done by hand. Labor shortages, especially for harvesting, limited agricultural production. The invention of the horse-drawn reaper in the 1830s, however, dramatically increased how much farmers could grow and helped pay the extra cost of using horses. A host of other mechanized devices soon followed to help with planting, cultivating, spraying, grinding and compressing. By 1900, huge combines pulled by 38-horse hitches were harvesting wheat in the Palouse region of western Washington.

In transportation, animals also made key technological developments possible. Horses and mules pulled boats on the Erie Canal, which linked Albany on the Hudson River with Buffalo on Lake Erie after 1825. Equine power thrived on the flat, hard surface of the towpath pulling heavy weight along a narrow, relatively friction-less surface of water. Whereas four horses could pull one ton of freight twelves miles per day on a rare good road, a single horse or mule could pull thirty tons per day on a canal boat. The Erie Canal slashed transportation costs, spurred industrial growth across upstate New York, opened the upper Midwest to settlement and agriculture, accelerated New England manufacturing, and caused New York City to outpace its seaboard rival cities permanently. But without animal power, the canal would have served little purpose and likely could not, and would not, have been constructed. Steamboats would not start to replace horses and mules until after the canal was widened in 1862.

Steam-powered railroads excelled at carrying goods and people between points. But when trains stopped, they were confined to their rails. Horse-drawn vehicles provided the flexible, self-propelled mode of transportation necessary to move people and goods from railroad depots to stores, warehouses and homes. During the Civil War, railroads moved troops and supplies to depots, but hundreds of thousands of horses and mules made actual army operations possible. Horse-drawn railway transportation also drove urban growth. The traditional “walking city” had a diameter of around two miles and covered about three square miles. Beginning in the 1850s, horse railways allowed cities to expand rapidly to an urban area of fifty square miles, Real estate developers paid to have horsecar lines connect new suburban properties to downtown. By 1880 the city of New York had 136 miles of horsecar lines employing 11,760 horses and mules.

The importance of animal power in the nineteenth century demonstrates how power technologies work together and that energy transitions are rarely linear. The transition away from animal power, which eliminated not just the direct use of animals but whole networks of producers and suppliers, was slow and it still has not ended. The transition occurred most quickly in American cities and suburban areas, and far more slowly in rural areas. Animal power remained in use in agriculture, delivery, and urban services until the early 1960s. To this day animal power remains vitally important in regions outside the United States, especially in Africa and Eurasia. There are other sites, even in the United States, where animal power remains the most effective and efficient choice. These include viticulture, because animal hooves do not pack down the earth and harm the vines, and selective logging, because horses excel in snaking logs out of the woods without destroying underbrush and other trees, and small-scale specialized agriculture, especially organic farming.

Cite this overview:

Greene, Ann Norton. “Overview: Animal Power.” Energy History Online. Yale University. 2023. https://energyhistory.yale.edu/animal-power/.

Library Items

Horses at War (gallery)

Horses participated in large numbers in the American Civil War, as well as World Wars I and II, but their role changed as they were increasingly integrated into mechanized warfare. This photo gallery suggests the massive number of horses that were part of the Civil War, and shows horses in increasingly specialized roles in later conflicts.

Horses in Agriculture (gallery)

Horses played a pivotal role in the agricultural transformation of the United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This gallery illustrates how new mechanical systems in agriculture evolved around horses and deployed them for tasks such as reaping and harvesting. The gallery demonstrates how horses remained an enduring feature in American agriculture during a period of rapid technological change.

Horses in the City (gallery)

Throughout the nineteenth century, urban transportation in the United States relied heavily on horses. Horses shared urban spaces with humans and powered new public transit networks. This gallery tracks the evolution of horse-powered transit from the heyday of horse carts and omnibuses to the early twentieth century, when horse-powered vehicles were elbowed out by electrical and cable cars.

How did cities have to adapt to accommodate the increasing numbers of urban horses? What changes in urban life did these horses make possible?

“Influence of Railroads Upon Agriculture,” Agriculture of the United States, 1860

Far from eliminating animal power as a source of energy, the dramatic expansion of the railroad system sharply increased the number of horses in the United States. According to this short essay from the 1860 agricultural census, the number of horses in the country increased by fifty-one percent between 1840 and 1860. Most of this growth occurred during the most rapid period of railroad expansion.

“The Position of the Horse in Modern Society,” The Nation, 1872

In 1872, an epidemic of equine influenza swept the United States, infecting horses and stalling horse-drawn public transportation. Such a noticeable disruption in the rhythms of urban mobility underscored the extent to which modern life still depended on animal power. The epidemic also spurred reflection on the place of the horse within modernity’s moral imaginary.

“Comparative Costs and Profits of Cable, Electric and Horse Railway Operation in New York City,” Street Railway Journal, 1898

By the late nineteenth century cityscapes and urban transportation were undergoing rapid change. The transit lines that previously relied partially or exclusively on horse-power were facing challenges from or being converted to electrical power. This article, published in the Street Railway Journal in 1898, examines the competition faced by horse-power at the outset of widespread urban electrification.

Horse and Mule Population Statistics

U.S. Census data shows how the horse and mule population of the United States grew dramatically between 1840 and 1920. In 1840, census records documented 4.3 million horses and mules. The population peaked in 1910 at 27.5 million, more than 600% higher than in 1840. What does the overall growth of horses and mules during the nineteenth century suggest about the relationship between animal power and the introduction of new mechanical technologies, including the steam engine?

Additional Reading

Derry, Margaret. Horses in Society: A Story of Animal Breeding and Marketing Culture, 1800-1920. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Ellenberg, George B. Mule South to Tractor South: Mules, Machines, and the Transformation of the Cotton South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

Greenberg, Dolores. “Energy Flows in a Changing Economy, 1815-1880.” Essay. In An Emerging Independent American Economy, 1815-1875, edited by Joseph R. Frese and Jacob Judd. Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy-Hollow Press, 1980.

Greenberg, Dolores. “Reassessing the Power Patterns of the Industrial Revolution: An Anglo- American Comparison.” The American Historical Review 87, no. 5 (December 1982): 1237–61.

Greene, Ann Norton. Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Mattfeld, Monica, and Kristen Guest, eds. Equestrian Cultures: Horses, Human Society, and the Discourse of Modernity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Kinney, Thomas A. The Carriage Trade: Making Horse-Drawn Vehicles in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Matthew S. Luckett. Never Caught Twice: Horse Stealing in Western Nebraska, 1850-1890. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020.

McShane, Clay, and Joel A. Tarr. The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Clay McShane and Joel Tarr. “The Decline of the Urban Horse in American Cities,” Journal of Transport History 24, no. 2 (September 2003): 177-198.

Mom, Gijs P. A., and David A. Kirsch. “Technologies in Tension: Horses, Electric Trucks, and the Motorization of American Cities, 1900-1925.” Technology and Culture 42, no. 3 (2001): 489–518.

Robichaud, Andrew A. Animal City: The Domestication of America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019.

Swart, Sandra. Riding High: Horses, Humans and History in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2010.

Author Bio

Ann Norton Greene is a historian of environmental and technological history in the History and Sociology of Science Department at the University of Pennsylvania, with expertise in animal history and energy history. Her book, Horses at Work: Harnessing Power in Industrial America (Harvard University Press, 2009), analyzes the use of horses in creating modern industrial society in late nineteenth and early twentieth century America.