Overview

Dante LaRiccia

Energy consumption changed significantly in the first decades of the twentieth century. Electrical lighting and utilities, once reserved primarily for public spaces and conspicuous sites of commerce and consumption, became an increasingly common domestic amenity. In 1910, one in seven American home were wired for electricity. By 1930, that number had risen to seven in ten. In the process, more Americans began learning about electric utilities and the range of domestic appliances that they powered.

Urban consumers were the first to enjoy domestic electricity in large numbers. High population densities packed more potential customers into smaller areas that didn’t require private utility companies to build far-reaching transmission lines. It was only later in the century, with the advent of government-sponsored electrification programs during the 1930s, that rural households joined their urban counterparts as common electricity users. But by the end of the 1920s, a majority of urban households had been wired with electricity.

Given these patterns of electrification, upper and middle class urban households were the first to adopt and experiment with domestic electricity and home appliances. Affluent urban households became targets for companies hoping to boost demand for electricity and electric appliances.

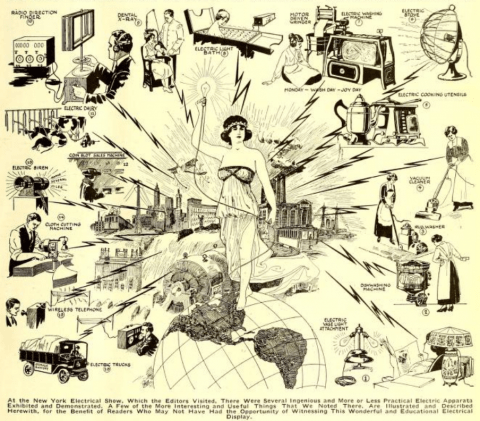

Utility companies and appliance makers launched promotional and educational campaigns during the early 1900s to stimulate consumer interest. Through advertising campaigns, home economics magazines, and promotional exhibitions, they sold the electrified household as the key to a better, more prosperous life. The 1920s in particular became a key period in the growth of advertising, as Americans spent more of their disposable income on consumer and domestic goods in the years following World War I. New popular magazines like Good Housekeeping and The Ladies’ Home Journal conveyed a new consumer ideal to American women.

Advertisers identified women as the principal audience for marketing an electrified domestic sphere. Tasked with overseeing domestic affairs, women could serve as the agents of electrification— homemakers who would actually adopt electrical appliances into everyday domestic routines.

As the primary sources in this unit illustrate, advertisers promised urban women higher levels of civilization and greater degrees of control within their homes. As a marker of technological “modernity,” electricity and electrical appliances made a “modern” household and a progressive woman. The modern woman, advertisers explained, let her electric appliances do the work. Labor-saving devices, including electric irons, dishwashers, and vacuum cleaners, would turn burdensome tasks into effortless chores. Electricity, many companies argued, transformed the home into a site where technological innovation and management would lessen womens’ burdens and raise the quality of domestic life.

This ideal of an electrified domestic sphere, however, also engendered changing expectations around the job of being a wife and mother. Social historians of technology like Ruth Schwarz Cowan and David Nye have shown how electricity altered gendered expectations around labor within the household.

Domestic electrification changed who performed domestic chores and with what frequency. Previously, for example, many families sent their laundry out for cleaning at a laundry service, or had a domestic servant wash the clothes. With an electric washing machine, however, laundry could become the job of wives and mothers. An electric vacuum similarly made it possible, and increasingly expected, for women to clean rugs and carpets on a regular basis, rather than expecting their male partners or hired help to perform the more strenuous task of hauling rugs outdoors once or twice a year to “beat” the dirt out of them. The idealized world of electrical labor-optimization thus concealed something quite different: mounting labor demands on women to maintain their homes at a new standard of cleanliness. As Nye notes, “Electrical conveniences made individual household tasks easier, but their number, frequency, and complexity increased.”

Scholars like Nye and the primary sources in this teaching unit show the benefits of integrating the histories of gender and energy. They also point toward a larger body of scholarship that interrogates how social and cultural constructions of gender, masculinity, and femininity relate to the material world and built environment. How else might we apply this approach to the study of consumption, technology, or energy?

This teaching unit explores cultural aspects of electrical use in the home, including the intersection of electricity with changing conceptions of femininity and the gendered nature of household labor.

Cite this overview:

LaRiccia, Dante. “Overview: Electricity Consumption: Culture, Gender and Power.” Energy History Online. Yale University. 2025. https://energyhistory.yale.edu/electricity-consumption-culture-gender-and-power/and Power – Energy History (yale.edu).

Library Items

Electricity in the Household

This article reveals how advertisers hoped to raise familiarity with electricity and electric appliances, particularly among the women that many assumed would make use of electric appliances. It describes some of the principles behind appliances like the electric egg poacher and coffee urn. Photographs, meanwhile, depict the electrified kitchen as a space far different from the “conventional” kitchen while also trying to dispel some of the “timidity on the part of some women to adopt electrical innovations.” What does this article reveal about changing notions of the “modern” home, and what does it tell us about how advertisers viewed women’s role in shaping consumer behaviors and domestic habits?

Jane Lane, “Come Out of the Kitchen,” July 1926

In this article, author Jane Lane entreats appliance salespeople to “come out of the kitchen.” Their pitches to women, she states, are almost entirely focused on the kitchen, the laundry room, the dining room–areas of domestic labor. But what of other, non-utilitarian electrical appliances. Could they not improve life in other areas of the home? Lane focuses on a simple technology, the lamp, to illustrate her point. She notes that electric lamps are not simply for illuminating the house more effectively, but also allow women to cultivate displays of taste and aesthetic refinement. How does Lane’s article construe women as more than domestic laborers? What other roles do they play in shaping domestic consumer trends?

The Home of a Hundred Comforts 1925

The home should be a place of comfort, and in 1925, the General Electric Company aimed to convince consumers that electricity was essential to that comfort. A fully wired home, this brochure argues, ensures that convenience and comfort are never far away. It takes readers on a tour of the idealized American home, one where electrical amenities are available in each room. This document is aspirational–although many homes enjoyed electricity by 1925, few reflected this stylized domestic vision. How does energy consumption relate to American middle-class desire and aspirations in this brochure?

Alice Carrol, “Selling the Electric Idea to the Ladies,” 1922

In this article for the National Electragist, author Alice Carrol describes important considerations in selling electric appliances to women. Salesmen, Carrol writes, need to convey the idea behind electric appliances, not just the attributes of the machine itself. She states that women require thorough demonstrations and firsthand experience with the improved capabilities of newer technologies and explanations for how they would change women’s home lives. How does the article represent female household managers as energy consumers? What does it suggest were the challenges of converting them to new electric technologies?

Truman E. Hienton and Kathryn McMahon, Turn the Switch: Let Electricity Do the Work, 1926

Farm life in the early 1900s was notoriously labor-intensive. In 1926, Purdue University’s Agricultural Experiment Station published a brochure that promised to lighten the load of rural families through the use of electricity. While it notes commercial utility, for example in milking cows and separating milk, it also lists a range of domestic applications aimed at the female managers of the home, from cooking and cleaning to lighting and radio entertainment. How does this source, aimed at rural audiences, contrast with advertisements targeting urban women as energy consumers?

Mrs. W. C. Lathrop’s Letter Thanking Thomas Edison for Electricity, 1921

In the early 1920s, electrical devices increasingly penetrated the American home, with a particular impact on the women who managed the household. In this 1921 letter to Thomas Edison, Mrs. W. C. Lathrop, the wife of a prosperous Kansas surgeon, thanked Edison for changing her life, helping to make her “a wife not tired and dissatisfied but a woman waiting who has worked faithfully believing that work is beneficial and who is now rested and ready to serve the tired man and discuss affairs of the day.” To be sure, Lathrop’s use of electricity far exceeded that of the typical Kansas housewife in 1921. Not until after the Rural Electrification Act in the 1930s and other efforts to expand access would many rural residents benefit from electrical devices.

How did the new devices reinforce Lathrop’s feminine domesticity?

How did electricity help relieve some of her drudgery and increase access to broader cultural opportunities?

Additional Reading

Bix, Amy Sue. “Equipped for Life: Gendering Technical Training and Consumerism in Home Economics, 1920-1980,” Technology and Culture 43, no. 4 (October 2002): 728-754.

Cowan, Ruth Schwartz. More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave. New York: Basic Books, 1983.

Goldstein, Carolyn M. Creating Consumers: Home Economists in Twentieth-Century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Hughes, Thomas. Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880-1930. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

Marchand, Roland. Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Moore, Abigail Harrison, and R. W. Sandwell, eds. In a New Light: Histories of Women and Energy. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2021.

Nye, David. Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880-1940. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1990.

Rose, Mark. Cities of Light and Heat: Domesticating Gas and Electricity in Urban America. University Park: Penn State University Press, 1995.

Strasser, Susan. Never Done: A History of American Housework. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2000.

Author Bio

Dante LaRiccia is a PhD candidate in the History Department at Yale University. His research explores the entangled histories of U.S. colonial expansion and the globalization of the carbon economy during the twentieth century.